Beyond API linting: writing rules about API changes

Aidan Cunniffe 2022-01-21

As developers writing code in the 2020s you are probably running multiple linters and formatters in your IDEs that help you avoid common programmatic errors and make the code more readable for your teammates.

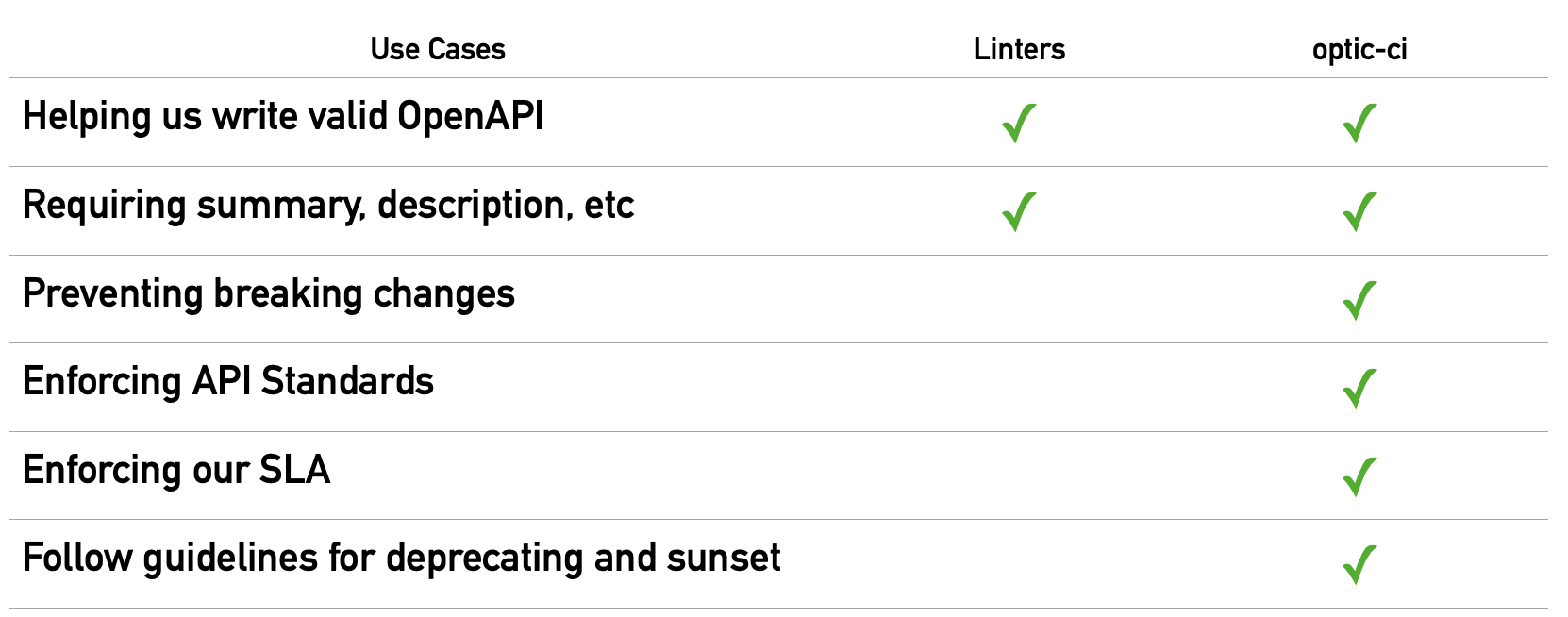

Linters are useful and a lot of teams we work with have tried to use API-specific linters as part of their API governance efforts. What they have found is that while API linting is great for making sure their specs are valid OpenAPI and basic standards are followed, in practice the things they really care about are not possible with linters. Linters can not prevent breaking changes, ensure they meet their SLAs, and have trouble enforcing the API style guides they've chosen.

Catch-22: Adoption, legacy and forwards only checks

The problem of linting code is very different than the problem of linting APIs. When you first add a linter to a legacy codebase — you will likely get 100s of errors. Left unresolved, those warnings create a lot of noise — how will you notice the issue count going from 100 → 101? To make linters a useful automated code quality check, you first have to go through your entire codebase and ignore or resolve each issue.

But what happens if we take the same thinking and apply it to our OpenAPI specification?

A code linter might tell you to change all your snake_case variable names to camelCase. That’s fine when the only ‘consumers’ of those variable names are also in your codebase, but APIs are external contracts. Changing them is always going to impact consumers.

If we turn a linter on that enforces our API standards it is almost a guarantee our existing API surface area violates some of the rules. As we saw, unlike updating our code, we can’t just go change an existing API’s contract just to get our rules passing.

- If we have a rule that says

POSTmust return a201status code and we had used200— changing each use of200is going to introduce breaking changes - If we have a rule that says all property names must be camelCase, fixing all the ones that are currently snake_case is also going to introduce breaking changes

This is the Catch-22 of automated API governance today and there are no good ways out. You could let certain rules fail — but this is noisy and makes it impossible to use the linter as a CI check. Or, as most teams have done, you could remove the rules that fail the legacy surface area, but that sounds a lot like a full retreat to me. It’s not good for the API, the team or the consumers.

If we want to use automated checks as part of our API governance efforts, we need tools that are built with the Catch-22 in mind. These tools are “forwards-only” throwing errors and making us meet the standards only in places where doing so does not result in breaking changes.

Static vs change-based checks

API linters are great for static checks. They can help us write valid OpenAPI, and ensure we have rich and useful summaries and descriptions throughout our specifications.

But API linters are not great at solving the most important problems facing API teams.

To catch breaking changes we need to look at two versions of the OpenAPI. Here API linters have an inescapable blind spot: they are only ever applied to one version of an API specification. For instance you call Spectral like this: spectral lint openapi.yaml. How would it ever find a breaking change if it does not know the previous API version?

Being able to see two versions of the OpenAPI specification also enables tooling that enforces your API standards “forwards-only” (not Catch-22). When you know what was in the last version of the specification you can choose to exempt existing surface area from your new standards rules. Now you can write rules with nuance: “All properties should be camelCase, but if a snake_case name was already in the API, do not ask the developer to change it.”

A new tool for authoring API Checks

We saw an opportunity to rethink how automated API checks could work and open source our efforts for the entire community to benefit from. Watch a video demo here (opens in a new tab). Our new optic-ci tool works differently than Spectral in these 4 key ways:

-

always compares two version of an OpenAPI file

optic-ci compare \ --from $GITHUB_BASE_REF:openapi.yaml \ --to $GITHUB_HEAD_REF:openapi.yaml -

runs rules when certain kinds of changes happen, instead of using JSON Path

-

uses rules that are written in code and are easy to test

-

support for important use cases linting can not solve

Examples of what is possible

One of my favorite examples of an optic-ci rule is this one which prevents a subtle breaking change: adding a required query parameter.

It’s breaking because clients would have to know to update their requests to include that required parameter or start getting unexpected 400s.

You could write a Spectral rule that prevents query parameters from being required, but that’s not actually what we want here. Some query parameters can be required, like a token, but we want all query parameters that are added after the API was published to follow this rule. Optic lets you write that rule in 4 lines of code:

request.queryParameter.added.must('not required', (queryParameter) => {

if (queryParameter.required)

expect.fail('adding a required query parameter is a breaking change')

});All breaking change rules are like the example above — they need more awareness of the API lifecycle to run at the right times.

Forwards-only governance

The first thing optic-ci does is compute a changelog between the two versions of the API. When you write a check in optic-ci you first select the kinds of changes that should trigger the rule. As one Beta user put it “spectral rules are written in the language of JSON Paths, writing Optic CI rules is writing in the language of API”s.

Optic’s approach of running the checks on the changelogs has a natural consequence — you can write rules in a way that will only apply your API standards to new surface area and changes. Let’s consider a rule for ensuring properties are camelCase. This rule runs on every property in the API and would fail on legacy endpoints with properties that do not follow this rule.

bodyProperties.requirement.must('have a camel case name', (property, context) => {

if (!isCamelCase(property.key)) expect.fail(`${property.key} is not camelCase`)

});But we can be clever — just change requirement to added and now the rule only applies to the new properties we add to our API:

bodyProperties.added.must('have a camel case name', (property, context) => {

if (!isCamelCase(property.key)) expect.fail(`${property.key} is not camelCase`)

});We think forwards-only governance is the key to making automated checks for API standards that help teams build better APIs without blocking them.

Get started

Optic CI is still in beta, and we're working towards a public release in coming weeks. If you'd like to partner to make optic-ci great, please join our beta. This has been really exciting to build! Stay tuned for more open source rulesets, case studies, and tools for authoring your own checks!

Try it yourself!

- Go turn on

optic-ciin your CI pipeline today! - Feedback welcome here (opens in a new tab)

- Support on Discord (opens in a new tab).

Want to ship a better API?

Optic makes it easy to publish accurate API docs, avoid breaking changes, and improve the design of your APIs.

Try it for free